what was a tactic used by the british to stall the india

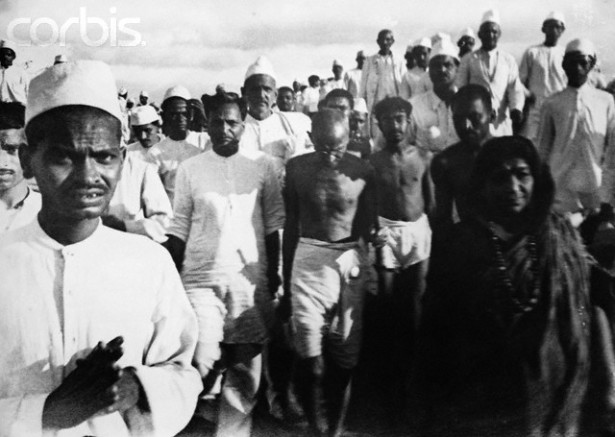

History remembers Mohandas Gandhi's Salt March every bit 1 of the groovy episodes of resistance in the by century and as a campaign which struck a decisive blow confronting British imperialism. In the early on morning of March 12, 1930, Gandhi and a trained cadre of 78 followers from his ashram began a march of more than 200 miles to the bounding main. Three and a half weeks subsequently, on April 5, surrounded by a oversupply of thousands, Gandhi waded into the border of the ocean, approached an area on the mud flats where evaporating water left a thick layer of sediment, and scooped upwards a handful of salt.

Gandhi's act defied a police force of the British Raj mandating that Indians buy common salt from the government and prohibiting them from collecting their own. His disobedience fix off a mass campaign of non-compliance that swept the country, leading to as many as 100,000 arrests. In a famous quote published in the Manchester Guardian, revered poet Rabindranath Tagore described the campaign'due south transformative impact: "Those who alive in England, far away from the East, have at present got to realize that Europe has completely lost her former prestige in Asia." For the absentee rulers in London, it was "a great moral defeat."

And yet, judging by what Gandhi gained at the bargaining table at the conclusion of the campaign, one can form a very different view of the table salt satyagraha. Evaluating the 1931 settlement made between Gandhi and Lord Irwin, the Viceroy of India, analysts Peter Ackerman and Christopher Kruegler take contended that "the campaign was a failure" and "a British victory," and that information technology would be reasonable to think that Gandhi "gave away the store." These conclusions have a long precedent. When the pact with Irwin was starting time announced, insiders within the Indian National Congress, Gandhi's arrangement, were bitterly disappointed. Future Prime Government minister Jawaharal Nehru, deeply depressed, wrote that he felt in his middle "a bully emptiness as of something precious gone, almost across recall."

That the Table salt March might at one time be considered a pivotal advance for the cause of Indian independence and a botched entrada that produced trivial tangible result seems to be a puzzling paradox. But even stranger is the fact that such a result is non unique in the world of social movements. Martin Luther King Jr.'s landmark 1963 campaign in Birmingham, Ala., had similarly incongruous outcomes: On the one paw, it generated a settlement that fell far short of desegregating the city, a deal which disappointed local activists who wanted more than merely pocket-sized changes at a few downtown stores; at the same time, Birmingham is regarded as one of the key drives of the civil rights move, doing perhaps more any other campaign to push toward the historic Civil Rights Human activity of 1964.

This seeming contradiction is worthy of test. Most significantly, it illustrates how momentum-driven mass mobilizations promote modify in ways that are disruptive when viewed with the assumptions and biases of mainstream politics. From start to finish — in both the way in which he structured the demands of the Salt March and the style in which he brought his campaign to a shut — Gandhi confounded the more conventional political operatives of his era. Yet the movements he led profoundly shook the structures of British imperialism.

For those who seek to understand today's social movements, and those who wish to amplify them, questions most how to evaluate a campaign'south success and when it is appropriate to declare victory remain as relevant as e'er. To them, Gandhi may still take something useful and unexpected to say.

The instrumental approach

Understanding the Salt March and its lessons for today requires stepping dorsum to look at some of the fundamental questions of how social movements effect alter. With proper context, i can say that Gandhi's actions were brilliant examples of the use of symbolic demands and symbolic victory. But what is involved in these concepts?

All protest actions, campaigns and demands accept both instrumental and symbolic dimensions. Different types of political organizing, all the same, combine these in different proportions.

In conventional politics, demands are primarily instrumental, designed to have a specific and concrete result inside the system. In this model, interest groups push for policies or reforms that benefit their base. These demands are carefully chosen based on what might be feasible to achieve, given the confines of the existing political landscape. Once a drive for an instrumental demand is launched, advocates effort to leverage their group'due south power to extract a concession or compromise that meets their needs. If they can deliver for their members, they win.

Even though they function primarily outside the realm of electoral politics, unions and customs-based organizations in the lineage of Saul Alinsky — groups based on edifice long-term institutional structures — approach demands in a primarily instrumental manner. As writer and organizer Rinku Sen explains, Alinsky established a long-continuing norm in community organizing which asserted that "winnability is of primary importance in choosing issues" and that community groups should focus on "immediate, concrete changes."

A famous instance in the world of community organizing is the need for a stoplight at an intersection identified by neighborhood residents every bit being unsafe. Only this is just i choice. Alinskyite groups might attempt to win better staffing at local social service offices, an end to discriminatory redlining of a item neighborhood by banks and insurance companies, or a new bus route to provide reliable transportation in an underserved area. Environmental groups might push for a ban on a specific chemical known to be toxic for wild fauna. A spousal relationship might wage a fight to win a enhance for a particular group of employees at a workplace, or to address a scheduling issue.

Past eking out modest, pragmatic wins effectually such issues, these groups improve lives and bolster their organizational structures. The hope is that, over fourth dimension, small gains will add together up to substantial reforms. Slowly and steadily, social change is accomplished.

The symbolic turn

For momentum-driven mass mobilizations, including the Salt March, campaigns function differently. Activists in mass movements must design actions and choose demands that tap into broader principles, creating a narrative most the moral significance of their struggle. Hither, the most important matter about a demand is not its potential policy affect or winnability at the bargaining table. Nigh critical are its symbolic backdrop — how well a need serves to dramatize for the public the urgent demand to remedy an injustice.

Similar conventional politicians and structure-based organizers, those trying to build protest movements also take strategic goals, and they might seek to address specific grievances as part of their campaigns. Merely their overall approach is more indirect. These activists are non necessarily focused on reforms that can exist feasibly obtained in an existing political context. Instead, momentum-driven movements aim to alter the political climate as a whole, irresolute perceptions of what is possible and realistic. They do this by shifting public opinion around an effect and activating an ever-expanding base of supporters. At their most ambitious, these movements take things that might be considered politically unimaginable — women'south suffrage, civil rights, the end of a war, the fall of a dictatorial regime, wedlock equality for same-sex couples — and plow them into political inevitabilities.

Negotiations over specific policy proposals are of import, but they come at the endgame of a movement, in one case public opinion has shifted and power-holders are scrambling to respond to disruptions that activist mobilizations have created. In the early stages, as movements gain steam, the key measure of a demand is not its instrumental practicality, simply its capacity to resonate with the public and arouse broad-based sympathy for a cause. In other words, the symbolic trumps the instrumental.

A variety of thinkers accept commented on how mass movements, because they are pursuing this more indirect route to creating alter, must be attentive to creating a narrative in which campaigns of resistance are consistently gaining momentum and presenting new challenges to those in ability. In his 2001 book "Doing Republic," Neb Moyer, a veteran social movement trainer, stresses the importance of "sociodrama actions" which "conspicuously reveal to the public how the power-holders violate gild's widely held values[.]" Through well-planned shows of resistance — ranging from creative marches and pickets, to boycotts and other forms of non-cooperation, to more confrontational interventions such as sit-ins and occupations — movements engage in a process of "politics every bit theater" which, in Moyer's words, "creates a public social crisis that transforms a social problem into a disquisitional public issue."

The types of narrow proposals that are useful in backside-the-scenes political negotiations are generally not the kinds of demands that inspire effective sociodrama. Commenting on this theme, leading New Left organizer and anti-Vietnam War activist Tom Hayden argues that new movements practice not arise based on narrow interests or on abstruse ideology; instead, they are propelled by a specific type of symbolically loaded issue — namely, "moral injuries that compel a moral response." In his book "The Long Sixties," Hayden cites several examples of such injuries. They include the desegregation of tiffin counters for the civil rights movement, the right to leaflet for Berkeley's Complimentary Speech Movement, and the farmworker movement's denunciation of the short-handled hoe, a tool that became emblematic of the exploitation of immigrant laborers because information technology forced workers in the fields to perform crippling stoop labor.

In some ways, these issues plow the standard of "winnability" on its head. "The grievances were not simply the material kind, which could be solved past slight adjustments to the condition quo," Hayden writes. Instead, they posed unique challenges to those in power. "To desegregate one lunch counter would begin a tipping process toward the desegregation of larger institutions; to permit student leafleting would legitimize a educatee vocalisation in decisions; to prohibit the short-handled hoe meant accepting workplace condom regulations."

Mayhap non surprisingly, the contrast betwixt symbolic and instrumental demands can create conflict betwixt activists coming from different organizing traditions.

Saul Alinsky was suspicious of actions that produced only "moral victories" and derided symbolic demonstrations that he viewed as mere public relations stunts. Ed Chambers, who took over as manager of Alinsky'due south Industrial Areas Foundation, shared his mentor's suspicion of mass mobilizations. In his book "Roots for Radicals," Chambers writes, "The movements of the 1960s and 70s — the ceremonious rights motility, the antiwar movement, the women'due south movement — were bright, dramatic, and attractive." Withal, in their delivery to "romantic problems," Chambers believes, they were too focused on attracting the attention of the media rather than exacting instrumental gains. "Members of these movements often concentrated on symbolic moral victories like placing flowers in the rifle barrels of National Guardsmen, embarrassing a politician for a moment or ii, or enraging white racists," he writes. "They ofttimes avoided whatever reflection most whether or not the moral victories led to any real modify."

In his time, Gandhi would hear many similar criticisms. Even so the bear upon of campaigns such as his march to the sea would provide a formidable rebuttal.

Difficult not to express joy

The salt satyagraha — or campaign of nonviolent resistance that began with Gandhi's march — is a defining example of using escalating, militant and unarmed confrontation to rally public back up and effect modify. It is also a case in which the use of symbolic demands, at least initially, provoked ridicule and consternation.

When charged with selecting a target for civil defiance, Gandhi's selection was preposterous. At least that was a common response to his fixation on the salt constabulary as the fundamental signal upon which to base the Indian National Congress' challenge to British rule. Mocking the emphasis on salt, The Statesman noted, "It is difficult not to laugh, and we imagine that will be the mood of most thinking Indians."

In 1930, the instrumentally focused organizers within the Indian National Congress were focused on constitutional questions — whether Republic of india would proceeds greater autonomy by winning "dominion status" and what steps toward such an arrangement the British might concede. The salt laws were a minor concern at best, inappreciably high on their list of demands. Biographer Geoffrey Ashe argues that, in this context, Gandhi's pick of salt equally a basis for a campaign was "the weirdest and most brilliant political challenge of modern times."

It was brilliant because defiance of the common salt police force was loaded with symbolic significance. "Next to air and water," Gandhi argued, "common salt is mayhap the greatest necessity of life." Information technology was a simple commodity that anybody was compelled to buy, and which the government taxed. Since the time of the Mughal Empire, the state'south control over salt was a hated reality. The fact that Indians were non permitted to freely collect table salt from natural deposits or to pan for common salt from the body of water was a clear analogy of how a foreign power was unjustly profiting from the subcontinent's people and its resources.

It was brilliant because defiance of the common salt police force was loaded with symbolic significance. "Next to air and water," Gandhi argued, "common salt is mayhap the greatest necessity of life." Information technology was a simple commodity that anybody was compelled to buy, and which the government taxed. Since the time of the Mughal Empire, the state'south control over salt was a hated reality. The fact that Indians were non permitted to freely collect table salt from natural deposits or to pan for common salt from the body of water was a clear analogy of how a foreign power was unjustly profiting from the subcontinent's people and its resources.

Since the tax affected anybody, the grievance was universally felt. The fact that it near heavily burdened the poor added to its outrage. The price of table salt charged by the regime, Ashe writes, "had a congenital-in levy — not large, just enough to cost a laborer with a family upwardly to two weeks wages a yr." It was a textbook moral injury. And people responded swiftly to Gandhi's charge confronting it.

Indeed, those who had ridiculed the entrada soon had reason to stop laughing. In each village through which the satyagrahis marched, they attracted massive crowds — with as many of xxx,000 people gathering to run across the pilgrims pray and to hear Gandhi speak of the need for self-rule. As historian Judith Brown writes, Gandhi "grasped intuitively that civil resistance was in many ways an practice in political theater, where the audience was as important equally the actors." In the procession'due south wake, hundreds of Indians who served in local administrative posts for the imperial authorities resigned their positions.

After the march reached the sea and disobedience began, the campaign accomplished an impressive scale. Throughout the country, huge numbers of dissidents began panning for common salt and mining natural deposits. Buying illegal packets of the mineral, even if they were of poor quality, became a badge of honor for millions. The Indian National Congress prepare its own salt depot, and groups of organized activists led nonviolent raids on the government table salt works, blocking roads and entrances with their bodies in an attempt to shut down production. News reports of the beatings and hospitalizations that resulted were broadcast throughout the world.

Soon, the defiance expanded to incorporate local grievances and to take on additional acts of noncooperation. Millions joined the boycott of British cloth and liquor, a growing number of village officials resigned their posts, and, in some provinces, farmers refused to pay land taxes. In increasingly varied forms, mass not-compliance took hold throughout a vast territory. And, in spite of energetic attempts at repression by British authorities, it continued month after month.

Finding issues that could "concenter wide support and maintain the cohesion of the motion," Brownish notes, was "no simple task in a country where there were such regional, religious and socio-economic differences." And notwithstanding salt fit the bill precisely. Motilal Nehru, begetter of the hereafter prime minister, remarked admiringly, "The only wonder is that no one else e'er thought of information technology."

Across the pact

If the pick of salt as a need had been controversial, the way in which Gandhi concluded the campaign would exist equally and then. Judged by instrumental standards, the resolution to the salt satyagraha fell short. By early on 1931, the campaign had reverberated throughout the country, notwithstanding information technology was also losing momentum. Repression had taken a toll, much of Congress' leadership had been arrested, and tax resisters whose property had been seized by the government were facing significant financial hardship. Moderate politicians and members of the business community who supported the Indian National Congress appealed to Gandhi for a resolution. Even many militants with the organization concurred that talks were appropriate.

Accordingly, Gandhi entered into negotiations with Lord Irwin in February 1931, and on March 5 the two appear a pact. On paper, many historians accept argued, it was an anti-climax. The central terms of the agreement hardly seemed favorable to the Indian National Congress: In exchange for suspending ceremonious disobedience, protesters being held in jail would be released, their cases would be dropped, and, with some exceptions, the government would lift the repressive security ordinances information technology had imposed during the satyagraha. Authorities would return fines collected past the government for revenue enhancement resistance, too as seized belongings that had not still been sold to third parties. And activists would be permitted to continue a peaceful boycott of British cloth.

However, the pact deferred discussion of questions nearly independence to futurity talks, with the British making no commitments to loosen their grip on power. (Gandhi would attend a Roundtable conference in London subsequently in 1931 to continue negotiations, only this meeting made trivial headway.) The government refused to carry an inquiry into police action during the protest campaign, which had been a house demand of Indian National Congress activists. Finally, and mayhap most shockingly, the Salt Deed itself would remain police force, with the concession that the poor in coastal areas would be allowed to produce salt in limited quantities for their own use.

Some of the politicians closest to Gandhi felt extremely dismayed past the terms of the understanding, and a diverseness of historians have joined in their assessment that the campaign failed to reach its goals. In retrospect, it is certainly legitimate to argue about whether Gandhi gave away also much in negotiations. At the aforementioned time, to gauge the settlement merely in instrumental terms is to miss its wider affect.

Claiming symbolic victory

If not by curt-term, incremental gains, how does a campaign that employs symbolic demands or tactics measure its success?

For momentum-driven mass mobilizations, in that location are two essential metrics past which to judge progress. Since the long-term goal of the motion is to shift public opinion on an issue, the first mensurate is whether a given campaign has won more popular support for a move'due south cause. The second measure out is whether a campaign builds the capacity of the motility to escalate further. If a drive allows activists to fight another twenty-four hour period from a position of greater forcefulness — with more members, superior resources, enhanced legitimacy and an expanded tactical arsenal — organizers can brand a convincing example that they take succeeded, regardless of whether the campaign has fabricated significant progress in closed-door bargaining sessions.

Throughout his career every bit a negotiator, Gandhi stressed the importance of beingness willing to compromise on non-essentials. As Joan Bondurant observes in her perceptive study of the principles of satyagraha, ane of his political tenets was the "reduction of demands to a minimum consequent with the truth." The pact with Irwin, Gandhi believed, gave him such a minimum, assuasive the motion to terminate the campaign in a dignified fashion and to set up for time to come struggle. For Gandhi, the viceroy's agreement to allow for exceptions to the common salt constabulary, even if they were limited, represented a critical triumph of principle. Moreover, he had forced the British to negotiate as equals — a vital precedent that would be extended into subsequent talks over independence.

In their own fashion, many of Gandhi's adversaries agreed on the significance of these concessions, seeing the pact as a misstep of lasting issue for imperial powers. As Ashe writes, the British officialdom in Delhi "ever afterwards… groaned over Irwin's move as the fatal corrigendum from which the Raj never recovered." In a at present-infamous speech, Winston Churchill, a leading defender of the British Empire, proclaimed that information technology was "alarming and also nauseating to see Mr. Gandhi… striding half-naked upwardly the steps of the Vice-regal palace… to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor." The move, he claimed, had allowed Gandhi — a human he saw every bit a "fanatic" and a "fakir" — to step out of prison and "[emerge] on the scene a triumphant victor."

While insiders had conflicted views nigh the campaign's result, the broad public was far less equivocal. Subhas Chandra Bose, one of the radicals in the Indian National Congress who was skeptical of Gandhi's pact, had to revise his view when he saw the reaction in the countryside. As Ashe recounts, when Bose traveled with Gandhi from Bombay to Delhi, he "saw ovations such as he had never witnessed earlier." Bose recognized the vindication. "The Mahatma had judged correctly," Ashe continues. "By all the rules of politics he had been checked. But in the people's eyes, the manifestly fact that the Englishman had been brought to negotiate instead of giving orders outweighed whatever number of details."

In his influential 1950 biography of Gandhi, still widely read today, Louis Fischer provides a most dramatic appraisal of the Salt March's legacy: "India was at present complimentary," he writes. "Technically, legally, zilch had changed. India was still a British colony." And yet, later on the table salt satyagraha, "it was inevitable that Britain should some 24-hour interval refuse to dominion India and that India should some twenty-four hours refuse to exist ruled."

Subsequent historians accept sought to provide more nuanced accounts of Gandhi'due south contribution to Indian independence, distancing themselves from a first generation of hagiographic biographies that uncritically held up Gandhi every bit the "father of a nation." Writing in 2009, Judith Brown cites a variety of social and economic pressures that contributed to Great britain's difference from Bharat, particularly the geopolitical shifts that accompanied the 2d Globe War. Still, she acknowledges that drives such as the Salt March were critical, playing central roles in building the Indian National Congress' organization and pop legitimacy. Although mass displays of protest lonely did non expel the imperialists, they profoundly altered the political mural. Civil resistance, Brown writes, "was a crucial role of the environment in which the British had to make decisions about when and how to get out Bharat."

Equally Martin Luther King Jr. would in Birmingham some three decades later, Gandhi accepted a settlement that had express instrumental value but that allowed the movement to claim a symbolic win and to sally in a position of strength. Gandhi'south victory in 1931 was not a terminal ane, nor was King's in 1963. Social movements today continue to fight struggles confronting racism, discrimination, economic exploitation and imperial assailment. But, if they choose, they can do so aided past the powerful example of forebears who converted moral victory into lasting change.

[Editor's notation: For more on how Gandhi won, read this follow-upwards article by Mark and Paul Engler on his strategy for success.]

Source: https://wagingnonviolence.org/2014/10/gandhi-win/

0 Response to "what was a tactic used by the british to stall the india"

Post a Comment